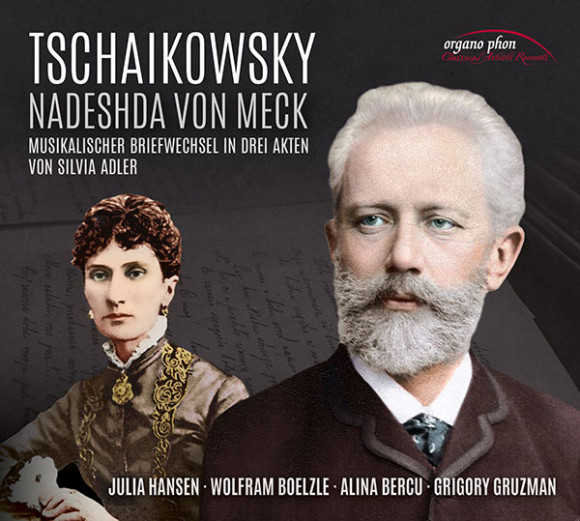

| CD 1 Im Fieberrausch der Töne – Tschaikowsky & Nadesha von Meck Erster Akt – "Landnahme" | 46:18 | ||

| CD 2 Im Fieberrausch der Töne – Tschaikowsky & Nadesha von Meck Zweiter Akt – "Idyll" Dritter Akt – "Verheerungen" | 65:43 | ||

| CD 3 Klavierwerke zum Hörbuch | |||

| 1 | Valse sentimentale op. 51, Nr. 6 | 5:04 B | |

| 2 | „April“ (Schneeglöckchen) aus: Die Jahreszeiten op. 37a, Nr. 4 | 2:55 G | |

| 3 | Meditation op. 72, Nr. 5 | 5:11 B | |

| 4 | „Mai“ (Weiße Nächte) aus: Die Jahreszeiten op. 37a, Nr. 5 | 3:54 G | |

| 5 | Dumka op. 59 | 8:56 B | |

| 6 | Dialogue op. 72, Nr. 8 | 4:10 B | |

| 7 | Wiegenlied „Lullaby“ op. 16 Nr. 1 Tschaikowsky/Rachmaninow | 5:04 B | |

| 8 | „Dezember“ (Weihnachten) aus: Die Jahreszeiten op. 37a, Nr. 12 | 4:35 G | |

| 9 | Chanson triste op. 40, Nr. 2 | 3:16 B | |

| 10 | Impromptu „Momento lirico” op. posthum | 2:57 B | |

| 11 | „Juni“ (Barkarole) aus: Die Jahreszeiten op. 37a, Nr. 6 | 4:49 G | |

| 12 | 2. Klavierkonzert op. 44 G-Dur (Auszug) | 1:33 B | |

| 13 | „Oktober“ (Herbstlied) aus: Die Jahreszeiten op. 37a, Nr. 10 | 4:36 G | |

| 14 | Sinfonie Nr.4, f-Moll op. 36, 2. Satz (Auszug) | 2:28 B/G | |

| 15 | Sinfonie Nr.4, f-Moll op. 36, 1. Satz „Schicksalsmotiv“ | 2:33 B/G | |

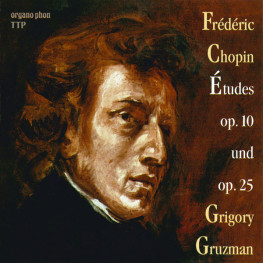

| Einspielung: B = Alina Bercu, G = Grigory Gruzman | |||

| Total | 62:04 |

++ THIS NEW ALBUM IS BEING RELEASED ON SEPTEMBER 18TH. PRE-ORDERS CAN BE MADE VIA E-MAIL TO info@organophon.de ++

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda von Meck wrote more than 1,200 letters to each other. Yet the two penfriends never spoke, and only ever caught sight of each other a few times and from a distance.

Their correspondence began in December 1876 and came to an abrupt and unexplained end in September 1890. Its almost 2,000 pages, however, document one of the most unusual love stories of the 19th century. It was a relationship at a distance, completely devoid of actual physical closeness, but which nonetheless reached an ecstatic spiritual intensity which transcended all conventions.

Nadezhda von Meck was the widow of a wealthy railroad tycoon, who died making her one of the richest women in Russia. For Tchaikovsky, she was a combination of patroness, muse and friend. She supported the composer with an annuity of 6,000 roubles, and promoted his music both in Russia and abroad. Their correspondence was preceded by a composition for violin and piano, which von Meck had commisioned from Tchaikovsky. The 45-year old widow lived in complete social seclusion with her 11 children (7 others had died early) in Moscow. She presided over a large household, including not only the family but also a retinue of governesses, private tutors and servants.

Tchaikovsky was 36 when they began to write to each other. His breakthrough as a composer had not happened yet, and he was earning his living teaching at the Moscow conservatorium. As an unmarried man with no offspring, he lived in constant fear that his concealed homosexuality might become public. His brief marriage with Antonina Milyukova had plunged him into a serious emotional crisis. He was torn on the one hand between fear and revulsion at the idea of physical contact with women, and on the other an immense longing for close domestic ties.

An early photograph in the Tchaikovsky museum in Klin reveals that the only picture on his desk was a photo of Nadezhda von Meck and her youngest daughter, Ludmilla. The two penfriends exchanged innumerable photos, both of themselves and their close relatives. As time passed, their letters began to read like those of a married couple. There was scarcely any subject that the two didn’t exchange views on. Questions of art, music and religion were discussed as naturally as family problems, professional matters or illness.

The hard and fast basis for their friendship was an agreement that they would never meet personally. With this foundation, there developed an intense exchange, which went far beyond a dialogue between cultivated friends. The relationship between Tschaikovsky and his patroness was like a platonic “amour fou”. Although it existed only on paper, it could hardly be surpassed for craziness and intensity.

For example, the two friends often holidayed in close proximity, just a few streets apart. They visited the same tourist attractions and strolled along the same streets, but always taking great care never to bump into each other. At the same time though, they exchanged impressions of their experience several times each day in hastily sent notes.

In Moscow, Tschaikovsky responded to an invitation from his friend to visit her house when she wasn’t there. He played her piano, looked at the pictures in her bedroom, smoked and chatted with her servant. After the visit, he immediately reported to her about the impression all this had made on him.

The fragile relationship between Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda von Meck could be illustrated by a simple image: a beautiful and rare bird perches in a garden, but flies away the instant one takes a step too close to it.

Anybody wanting to admire it at leisure has to know where the invisible line runs that must not be crossed. Often enough, Nadezhda von Meck got dangerously close to the line in her letters. The exchange of letters mirrors spiritual kinship and idyllic love as well as a dramatic struggle for closeness. From as much distance as possible, they wrestle over every centimetre of spiritual sovereignty. The correspondence derives its tension especially from the fluctuation of emotional dominance, where each partner defies any attempt at an unambiguous assignment of roles. One

witnesses a campaign of conquest without territory and with continually changing battle lines. It remains a mystery why Nadezhda von Meck suddenly broke the correspondence off after 14 years.

By selecting certain letters, I wanted to make the unusual nature of the relationship between the two correspondents the focus of attention. The actual nature of this relationship was always uppermost in my mind.

Silvia Adler

There are no reviews yet.